Public Charge 101

August 2019 | Click here to View the “Public Charge 101” Fact Sheet (PDF)

On April 24, the Supreme Court declined pleas from states to reexamine its January decision related to implementation of the public charge rule. Attorneys general from New York, Connecticut, Illinois, and Vermont appealed to the Court to temporarily pause the public rule until the COVID-19 pandemic is over. The justices did not weigh in on the merits and left the door open to the AGs seeking relief in lower courts.

COVID-19 Guidance: USCIS issued policy guidance stating that seeking testing or treatment for COVID-19 will not impact public charge admissibility. In addition, USCIS clarified that “if the alien is prevented from working or attending school, and must rely on public benefits for the duration of the COVID-19 outbreak and recovery phase, the alien can provide an explanation and relevant supporting documentation. To the extent relevant and credible, USCIS will take all such evidence into consideration in the totality of the alien’s circumstances.”

***

Pursuant to Section 212(a)(4) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA), any individual seeking admission to the United States, or applying for green card, is ineligible if he/she is likely to become a “public charge.”

What is a “public charge”?

A “public charge” is an individual who is likely to become dependent on government benefits for his/her survival.

Section 212(a)(4) does not precisely define “public charge,” but requires, as part of the public charge inadmissibility determination, consideration of the alien’s: (1) Age; (2) Health; (3) Family Status; (4) Assets, Resources, and Financial Status; and (5) Education and Skills.

Why do we have public charge laws?

The colonists who settled the United States firmly believed that, except in exigent circumstances, failing to care for oneself and one’s family imposed an unfair burden on one’s

neighbors. Able-bodied members of the community were not typically assisted by taxpayers unless they also worked. Only children, the elderly, and the sick were supported at taxpayer expense without being required to work.

Public charge laws guaranteed that those who were not willing to work in order to support themselves did not overburden the community. They also ensured the availability of adequate resources to care for those truly in need.

Is this something new under the Trump administration?

No, public charge laws were a central feature of public policy from the time the Thirteen Colonies were first founded. The first public charge laws were enacted in 1645, when Massachusetts was still a colony. Those laws prohibited the importation of new colonists who were likely to become public charges. However, they also prohibited the movement of “paupers, toss-pots and ne’er-do-wells” from one colony to another. Rather than a condemnation of the poor, such legislation reflected the colonists’ belief that citizens were obligated to care for themselves, rather than placing the burden for their sustenance on their neighbors.

Colonial notions of self-sufficiency and financial responsibility carried over into the new republic. Eastern seaboard states, such as Massachusetts and New York, passed laws limiting the immigration of people likely to become public charges. They also charged steamship companies “head taxes” for every new passenger/immigrant to help pay for costs associated with aliens who ended up in state-funded poor houses. Shipping companies opposed such head taxes in the name of “free immigration and commerce.” Laws excluding paupers and the poor were a response to “assisted immigration,” i.e. the practice of European governments financing the migration of their poorest inhabitants across the Atlantic.

The first comprehensive federal immigration law, the Immigration Act of 1882, barred the admission of “any person unable to take care of himself or herself without becoming a public charge.” And, for well over a century, immigrants’ admissibility to the United States was determined primarily based on their prospective ability to earn a living. During the period of the first Great Wave, new categories were added to the public charge exclusion list, including: “professional beggars” (1903), those with a “mental or physical defect being of a nature which may affect the ability of such an alien to earn a living” (1907), and “vagrants” (1917). The Immigration Act of 1891 also made public charges and other members of the above excludable classes subject to deportation. The Immigration Act of 1917 extended the deportability period for aliens who became public charges “from causes not affirmatively shown to have arisen subsequent to landing” to five years. From 1882 to 1924, public charge exclusions were enforced primarily by immigration officers at ports of entry; this responsibility shifted to consular officials overseas after the implementation of the visa system in 1924.

The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 – which remains the basis of our current immigration law – maintained the provision that immigrants who became public charges within five years of arriving in the U.S. (so long as the cause could not be proven to have arisen after their arrival in the country) could be removed at any time.

In 1996, Congress passed the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PRWORA), which reformed our welfare policies, and the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA), which reformed our immigration system. The most important relevant aspects of the 1996 reforms are enumerated below.

Is self-sufficiency still a primary goal of U.S. immigration policy?

It should be. In 1996 Congress referred to “a compelling government interest to enact new rules for eligibility and sponsorship agreements in order to assure that aliens be self-reliant in accordance with national immigration policy.” It acted on that compelling interest by:

- Requiring sponsors of immigrants to assume financial responsibility for that immigrant.

- Requiring petitioners to sign a legally binding affidavit of support acknowledging their financial responsibility.

- Empowered states to deny welfare benefits to most illegal aliens and lawful immigrants.

- Barred illegal aliens from welfare programs that receive federal funds.

- Rendered immigrants ineligible for means-tested federal benefits for five years after admission to the United States.

Why is it necessary to reinforce the public charge rules?

In response to complaints from “immigrant rights” groups that the public charge rules were “draconian” and “anti-immigrant,” the Clinton administration backpedaled, redefining “public charge” to allow both legal and illegal aliens to collect most types of welfare benefits without penalty.

This action imposed a heavy financial burden that American taxpayers still shoulder to this day. Subsequently, the Obama administration further broadened the Clinton-era guidelines, making even more benefits available to foreigners who never paid into our social safety net.

What is the Trump administration doing to keep immigrants off public assistance?

The Trump administration promised to restore integrity to the public charge grounds of admissibility and deportability. It is also encouraging USCIS staff to consider the use of public benefits a during the naturalization process.

In October 2018, the Trump administration proposed a rule change concerning inadmissibility on public charge grounds. The essence of the proposed rule is that “aliens who seek adjustment of status or a visa, or who are applicants for admission, must establish that they are not likely at any time to become a public charge, unless Congress has expressly exempted them from this ground of inadmissibility or has otherwise permitted them to seek a waiver of inadmissibility.” The exempted groups include asylees, refugees, and the victims or trafficking or crime. The rule also defines a “public charge” as an alien who receives one or more public benefits, be they cash benefits (e.g. SSI payments, SNAP, or TANF) or non-monetizable ones (such as Medicaid or subsidized housing). However, the receipt of designated public benefits would not necessarily make an alien likely to become a public charge. Rather, the alien’s case would be evaluated on the basis of whether he/she is likely to become a public charge based on the totality of the circumstances by weighing all positive and negative factors. To further address the “public charge” problem, in May 2019, President Trump signed a memorandum that will finally enforce a 23-year-old provision requiring sponsors of legal immigrants to reimburse the government for any social services the immigrant uses in the U.S.

On August 14, 2019, the Trump administration published a new public charge rule, which replaces the 1999 Interim Field Guidance on Deportability and Inadmissibility on Public Charge Grounds. The Department of Homeland Security has revised and broadened the definition of “public charge” to incorporate consideration of more kinds of public benefits received by immigrants.

The rule was initially supposed to go into effect on October 15, 2019. Shortly before that time, several federal courts prohibited (enjoined) DHS from implementing it. However, the U.S. Supreme Court stayed the last remaining injunction on February 21, 2020, thereby allowing the final rule to go into effect pending the resolution of litigation on the merits of the case.

It defines the term “public charge” as an individual receiving one or more designated public benefits for more than 12 months, in the aggregate, within any 36-month period. In this case, the receipt of two benefits in one month counts as two months. The rule also defines the term “public benefit” to include any cash benefits for income maintenance, Supplemental Security Income (SSI), Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF), Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program (SNAP, or “food stamps”), most forms of Medicaid, and certain housing programs.

Certain non-immigrant aliens would also be ineligible to change their status or extend their stay if they have received designated public benefits above the designated threshold after obtaining the non-immigrant status they seek to extend or from which they seek to change. The rule does not apply to certain categories, including active-duty members of the military and refugees or asylees. The new rule is a step in the right direction and represents a common-sense approach to immigration reform.

Why is this so important?

America’s social safety net is financed by taxpayers. Carelessly providing millions of dollars in benefits to people who never paid into our system is a recipe for financial disaster.

Opponents of the idea that immigrants should be self-sufficient would have us believe that only a small number of immigrants use public assistance programs and that they do so only temporarily. But that simply doesn’t add up with the available data.

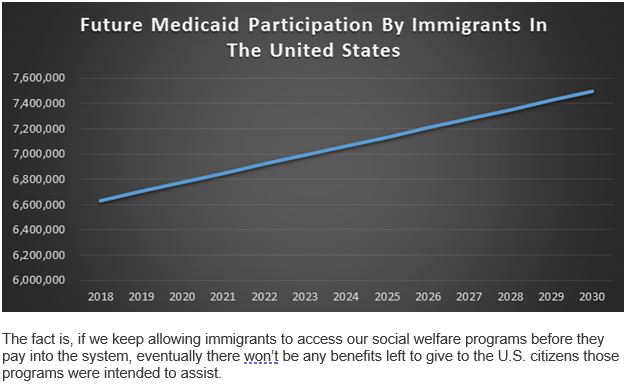

According to a report released by the Center for Immigration Studies (CIS), the reality is that almost two-thirds (63 percent) of all immigrant-led households currently use at least one welfare program – compared to only 35 percent of native households. The same CIS report shows that forty-eight percent of households headed by immigrants who have been in the country for more than two decades continue to access at least one welfare program. And, according to data from the Census Bureau’s Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP), by the year 2030, more than 13 million immigrants will use welfare and 7.5 million immigrants will be enrolled in Medicaid – placing a major strain on an already ailing program.

For more information read:

- FAIR’s Comment on Public Charge Rule

- a href=”https://thehill.com/opinion/immigration/420710-congress-can-render-the-new-public-charge-rule-moot”>Congress Can Render the New ‘Public Charge’ Rule Moot

- Opinion: Barring Immigrants Who are Likely to Become Public Charges is Good Policy

- Immigration Under Trump: If You Can’t Afford It, Don’t Come