Automated Entry-Exit System

April 2012

Every year, millions of foreigners enter the U.S. as “nonimmigrants” (visitors or workers) for a limited period. Although they are expected to return home at the end of their visit, there is no effective means for detecting those who do not. The number of those who have not left the United States upon the expiration of their visa is estimated to be between 4-5.5 million people, which accounts for 30-40% of all illegal immigrants in the United States.1Worse yet, overstay data has not been regularly submitted to Congress since 1994.

Without coordinated entry-exit controls, the U.S. has no way of noticing whether a visitor unlawfully overstays his/her entry permit. In the absence of such a system, terrorists and other criminals can more easily enter the U.S. and remain to threaten us from within. Several of the September 11th hijackers overstayed their visas, remaining undetected through the years it took them to plan their attacks.

Mandates and Delays

Registration of visitors is commonplace in virtually every comparable country. In the U.S., requirements that foreign visitors register with the government are not new; some form of registration has been required since 1940. Sections 261 through 266 of the Immigration and Nationality Act already require that aliens staying longer than 30 days register and be fingerprinted.

Congress had mandated an entry-exit system in 1996 (as part of the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act, or IIRAIRA), but due to objections from the tourism industry and others, full implementation has been delayed.

After the September 11th attacks, when it became clear that the nation’s ability to track foreign visitors was critical to national security, the matter took on more urgency. The Border Security Act of 2002 again mandated the implementation of a computerized entry-exit database — but not until 2005.

As an interim measure, a new registration program called NSEERS (National Security Entry-Exit Registration System) tracked males aged sixteen or older who were not naturalized citizens or permanent immigrants and who came from certain countries considered terrorist risks. They were required to register with the federal government and submit photographs and fingerprints to be checked against a database of known criminals and terrorists. Failure to register could have resulted in deportation and criminal charges.

A New System Emerges

As the full entry-exit system — called the U.S. Visitor and Immigrant Status Indication Technology (US-VISIT) system — began implementation, it replaced NSEERS altogether.

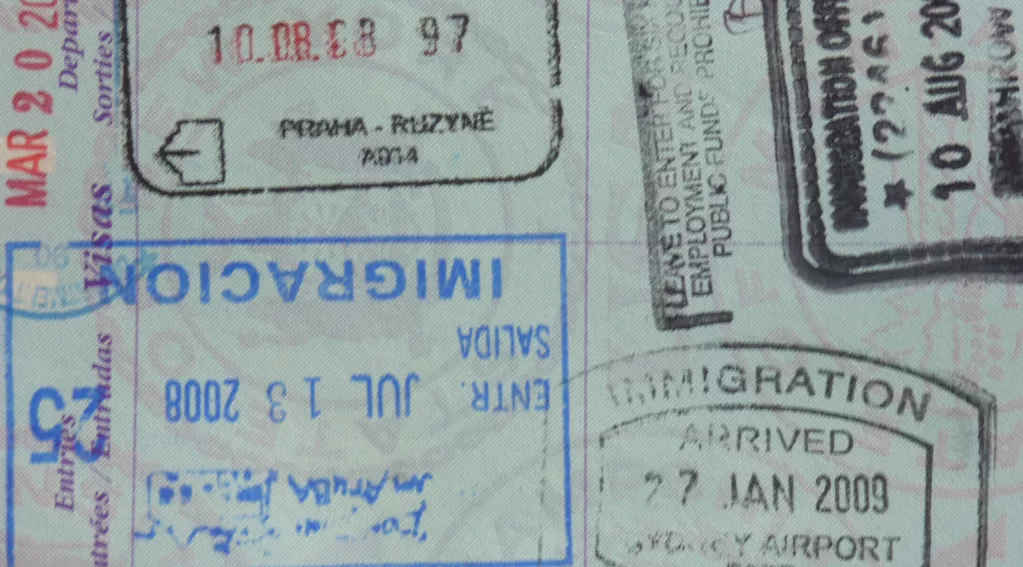

US-VISIT creates an electronic check-in/check-out system for foreign visitors, including students, tourists, and business travelers, and will require the use of at least two biometric identifiers, such as photo identification and fingerprint records, when entering and leaving the country. The program was introduced at seaports, international airports, and land border crossings. It began to collect biometric information at air and sea ports in 2004, and on land in 2007.

Chink in the Armor

For the US-VISIT system to be fully effective, it must correct two crucial errors in its system. First, it must collect biographic and biometric data on allforeign visitors. As it stands now, some remain exempt from participating in US-VISIT, such as some classes of Mexican and Canadian citizens and other foreign nationals admitted under certain visas. If we are not collecting biographic and biometric data on all visitors, the system is at risk of being undermined by offering an opportunity to terrorists, criminals, and unwanted aliens to enter the country under these exemptions.

A second error in US-VISIT is that it does not track whether or not visitors are actually leaving. Customs and Border Patrol does not effectively collect issued departure forms because these forms are turned in of the non-immigrants’ own accord. As of 2011, there is still no way to be certain that visitors are leaving when their visa expires without personally tracking the individual down through biographic information.

In FY 2004-2010, ICE conducted 34,700 overstay investigations. Of these investigations, 77% either: 1) left the country, 2) updated their status, 3) or cannot be found. For those who departed or updated their status, this is a waste of resources when DHS could easily collect such information if there was an exit tracking system in place. For those who cannot be found, they present a dangerous security threat to the United States as they may have disappeared within our borders. Senator Susan Collins made clear the threat of lax screening of foreign visitors: “As has been noted often, the terrorists only have to get it right once. DHS and its partners have to be right every single time, or we will suffer the devastating consequences.”2 To prevent these risks, one of the most logical places to begin an exit program would be at airports, where biometric collection technology is already in place.

Another possible means to create a more manageable system would be shared data collection responsibility with Canada. Under this proposal, which has been under discussion for several years, U.S. and Canadian authorities would integrate entry-exit systems (where one’s entry would be another’s exit) and cross-border law enforcement.

Accommodating Commercial Interests

Under the Western Hemisphere Travel Initiative, four programs were created to accommodate commercial interests and trade. NEXUS (for U.S.-Canada), SENTRI (for U.S.-Mexico), and FAST (for commercial truck drivers) are designed for land and sea travel. The fourth program, Global Entry, adds for the allowance of air travel. These IDs are designed for those who traverse the border frequently, and are issued after the applicant successfully completes a personal interview and submits biographic and biometric information.

While these programs provide convenience for frequent travelers, it should be noted that 75% of entrants to the United States come by land, and between 700,000 and 900,000 border crossing cards are issued each year. Any accommodations in the data collection system at land ports of entry for local visitors should be carefully evaluated and re-evaluated to determine the possibility for exploitation under worst case scenarios. While international trade, tourism, and cross-border travel are extremely important, they cannot be allowed to override security.

Footnotes and endnotes

- Visa Security: Additional Actions Needed to Strengthen Overstay Enforcement and Address Risks in the Visa Process”, U.S. Government Accountability Office, September 2011.

- Senator Collins, Sept. 7, 2011 Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee Hearing on Challenges Facing the Department of Homeland Security